Why you should read fiction in times of war

And in times of peace, to avoid war

Reading time: 5 min

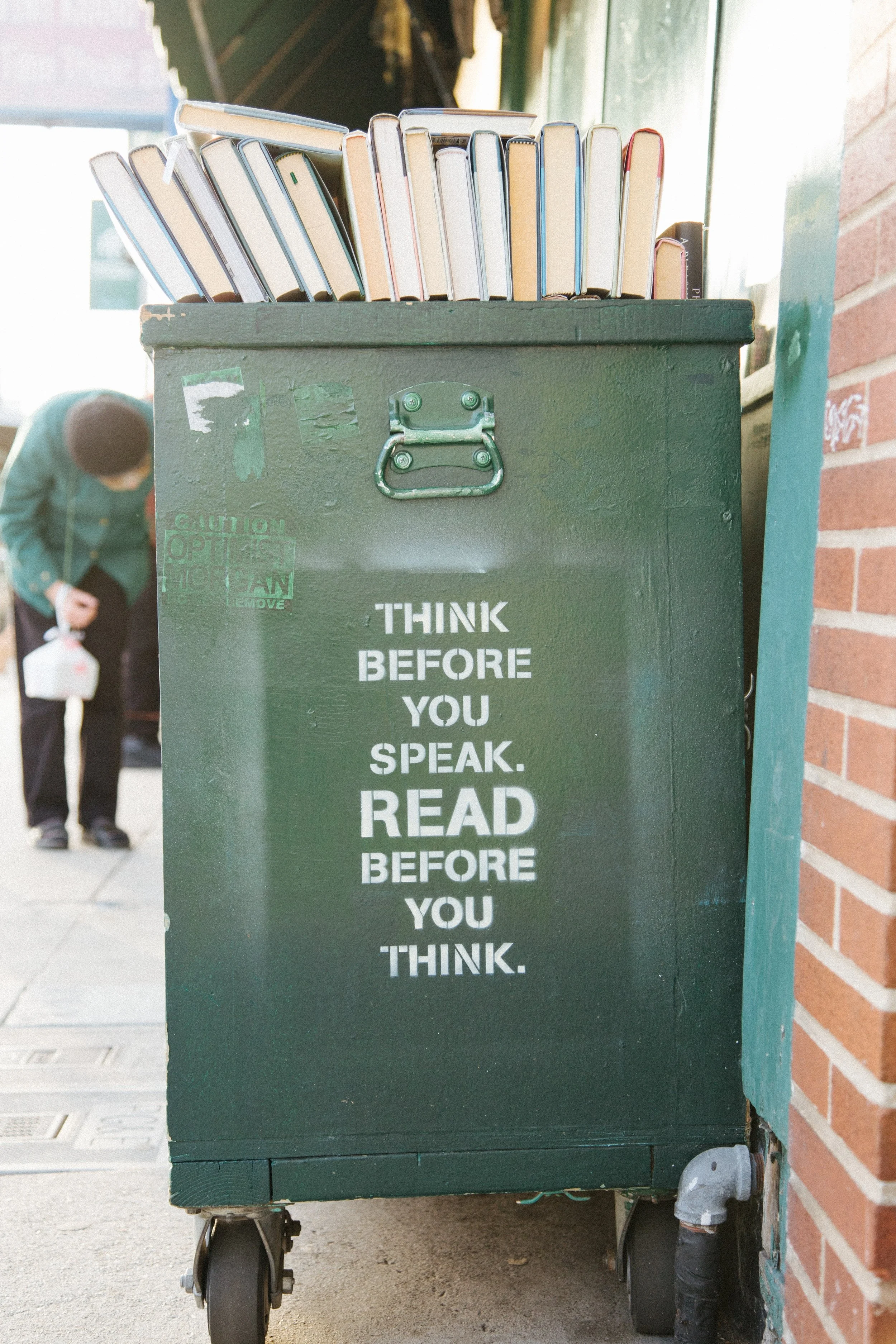

Photo by Leonardo Burgos on Unsplash

Foster kids and emotional intelligence

One of my best friends used to work as a support worker in a difficult care home, and he had the most entertaining stories about what happened in there.

Some of them were funny, like the time his partner got punched in the balls because he failed to spot early signs of escalation during an argument; some of them were really, really sad.

Some others, though, were more like a window into what it means to be human; a picture of the depths of our downfalls and the brightness of our hope.

Photo by Arwan Sutanto on Unsplash

One day, he told me, he was preventing a child from smashing all the dishes in their kitchen, and the kid didn’t take it well. After some back and forth, that child, incapable of containing his frustration, spat on my friend’s face. He kept his cool—stoic, almost—then wiped the spit off his cheek and rubbed it onto the kid’s sleeve.

“You can’t do that!” the kid cried.

“Why not?”

“Because it’s disgusting!”

The kid was so disconnected from reality, so unable to empathise with someone else, that he couldn’t bear the idea of having his own spit drying on his clothes after being removed from my friend’s face.

Foster kids cannot be blamed. They don’t know better. They struggle with abandonment issues, with authority. They’ve probably lived through more traumatic events than most of us will ever endure, and those moments—often revolving around spit, or punches, or broken glass—are teachable moments. Those are the moments that will define them as adults.

The importance of reading fiction

Children are able to understand that spit on themselves is as disgusting as their own spit on someone else only if they’ve been exposed to one of those two situations:

It happened before, and a loving parent had taken the time to explain what they should or shouldn't do.

They’ve seen it happen in a story.

Photo by Jerry Wang on Unsplash

Reading has already been proven to be the best trick to play on your brain when you can’t actually do the thing you’re reading about.

Reading fiction, in particular, because of this superpower the written word has over our brains’ plasticity, is the best way to build emotional intelligence.

As Rita Carter says in her beautiful TED Talk; just by strengthening those new neurological pathways forming in your brain when you read good fiction, it’s almost as if you’re experiencing the characters’ emotions.

No wonder we get so involved when reading Wuthering Heights. No wonder we fight back tears reading Beloved, or at the end of Life of Pi. No wonder we can’t read The Shining by ourselves, in the dark, during a stormy night.

Reading the pain, joy and fears of those characters teaches us about our own pain, joy and fears, and about pain, joy and fears of others.

Matt Haig. Credit: Twitter

I can’t even begin to understand the struggles of a single, pregnant woman; the judgement, the shame, the unfairness, but Letter to a child never born helped me. I hope I’ll never have to go through the horrors of fleeing from a country at war, but reading The kite runner was invaluable to feel closer to those who have.

Authors like Matt Haig have done wonders to normalise mental illnesses, and I’m glad he went mainstream with his last novel: The midnight library, because the world, especially now, needs an urgent shipment of kindness.

A dangerous lack of empathy

I’m not saying there are no assholes reading fiction, absolutely, nor that if we as a species read more fiction we wouldn’t have wars—I’m not that naïve, though I’d like to be—I’m just saying that it would help to be a little nicer to each other.

At the very beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I’ve read this horrific article on The Guardian, describing how Polish nationalists have targeted non-European refugees fleeing from Ukraine into Poland.

Imagine being a student at your first experience abroad. Imagine waking up to the sound of rockets and explosions, imagine being scared for your life. Imagine packing the few things you think are going to be necessary and fleeing in the middle of the night, hoping to find a spot among the thousands who are doing the same. Imagine being unsure whether or not you’ll ever reach the border, imagine not knowing if you’ll ever see your family again. And then, imagine making it, hungry, exhausted, cold and weak, but finally safe into Poland and, immediately, being harassed, attacked or even beaten for the simple reason that you don’t look like the others around you.

Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash

I have no right to judge, but I bet none of those Polish nationalists have ever read a good novel.

Maybe they’ve read propaganda, maybe they’ve watched action movies, but not a novel; not an old-fashioned book.

In a sense, they’re no different from my friend’s Foster kids, if it wasn’t for the fact that they bear responsibility for their actions.

Art, and especially stories, are not optional for human development. Ask the cavemen, taking time out of hunting to paint scenes on the walls of their shelters. Ask the Greeks, who invented an entire mythology to teach youngsters the highs and lows of human emotions.

But people are quick to forget. And that’s dangerous, because it leads to the same suffering, over and over again.

And that’s why we should all read more.

Alla prossima.

Photo by Max Kukurudziak on Unsplash